”25 de Abril” - From Carnations to Cameras

How the lens of history connects Portugal's past to America's present.

Today marks the 51st anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, when Portugal emerged from the shadows of one of Europe's longest-running dictatorships. As someone born in the US but raised in Porto, Portugal, the 25 de Abril has always held a somewhat mystical meaning for me. My childhood was filled with stories of the “antes” and “depois”, the “before” and “after”, that divided Portuguese history into darkness and light.

As a child, these stories of Portugal's dictatorship felt like ancient history, events that existed in a time far removed from my own reality. Only now do I realize that the shadows of the dictatorship were as close to my childhood as the 2010s are to us today. This temporal proximity is jarring to say the least. What seemed like distant tales from another era when I was a kid, were in fact the recent memories of people all around me. The pendulum swings faster than we imagine.

Growing up in Portugal during the post-revolution years, I absorbed the collective memory of a nation reborn. I would hear stories from my grandparents of the Estado Novo1 regime not as distant history but as lived experience, the censored newspapers, the feared secret police (PIDE), the enforced silence around political matters. They described April 25, 1974, with a reverence reserved for sacred moments: the military coup that bloomed into a popular uprising, soldiers with carnations in their rifle barrels, and the breath of freedom after decades of suffocation.

Now, as an american photographer living in the US and witnessing the current political developments under Trump's administration in 2025, these memories have taken on new, unsettling resonance. The parallels between Portugal's authoritarian past and America's concerning present have become too striking to ignore.

The Estado Novo regime (1933-1974) under António de Oliveira Salazar and later Marcelo Caetano was characterized by systematic control of information and expression. With the slogan “Deus, Pátria, e Família” (God, Fatherland, and Family), the regime wrapped itself in traditional values while methodically dismantling democratic freedoms.

What made the Estado Novo particularly insidious was its veil of normalcy. It wasn't the brutal spectacle of some dictatorships but a quiet, pervasive control. Newspapers operated under strict censorship, with editors submitting content for approval before publication. Books were banned not just for political content but for “moral” reasons as well. Universities became places where critical thinking was dangerous, and the education system was redesigned to produce compliance rather than questioning.

This system of control extended into culture, with artists, writers, and musicians facing stark choices: conform, create in exile, or face consequences. The famed fado singer Amália Rodrigues saw songs banned from radio. Modern painters whose work hinted at dissent often had to exhibit abroad. In 1972, three Portuguese women writers were prosecuted simply for publishing a book2 (Novas Cartas Portuguesas) that the regime deemed “immoral”, their actual offense was criticizing Portugal's treatment of women.

Fast forward to America in 2025, and the echoes of these tactics are becoming disturbingly familiar. President Trump has returned to office with an explicit agenda of reshaping America's information landscape. On his first day back in office, he signed an executive order supposedly aimed at “restoring freedom of speech and ending federal censorship,” but in practice, this has meant dismantling efforts to combat disinformation while simultaneously attacking critical media.

The administration has taken aim at various pillars of independent information and cultural expression:

The Free Press: Trump has intensified his rhetoric against journalists, referring to critical media as “enemies of the people.” His administration has restricted access to White House press briefings for certain outlets and has sued major news organizations over unfavorable coverage. When journalists were attacked during the January 6th riots, Trump pardoned at least 13 individuals involved in those assaults, sending a chilling message about the consequences of reporting that displeases those in power.

Scientific Inquiry: In a sweeping move, the administration has cut funding for over 380 National Science Foundation grants, targeting research involving diversity, equity, inclusion, or the study of misinformation. Since January 2025, NIH funding has dropped by more than $3 billion compared to the same period last year, a nearly 60% decline. This has affected research on cancer, Alzheimer's, and other diseases that Trump specifically promised to fight during his campaign. The message is clear: certain lines of inquiry are now unwelcome if they conflict with the administration's political narrative.

Arts and Culture: An executive order effectively dismantled the Institute of Museum and Library Services, while the National Endowment for the Arts now requires grant applicants to swear not to promote “gender ideology” in their work. Museums and libraries, the keepers of our cultural memory, face defunding precisely because, as one union president noted, they “contain our collective history and knowledge... the heart of our communities.”3

The Rule of Law: Trump has publicly attacked judges who rule against him and issued executive orders sanctioning law firms whose lawyers were involved in investigations of him. Inside the Department of Justice, career attorneys who prosecuted Trump's allies have been fired or sidelined. As Congressman Jamie Raskin observed, "No other president in American history has stood in the Department of Justice to proclaim an agenda of criminal prosecution and retaliation against his political foes."4

These developments represent a clear pattern of institutional erosion that feels eerily familiar to anyone who has lived through or studied how democracies slide into authoritarianism. They remind me of the gradual tightening of control that characterized Portugal's Estado Novo, not an immediate, violent takeover, but a creeping suffocation of independent voices and democratic institutions.

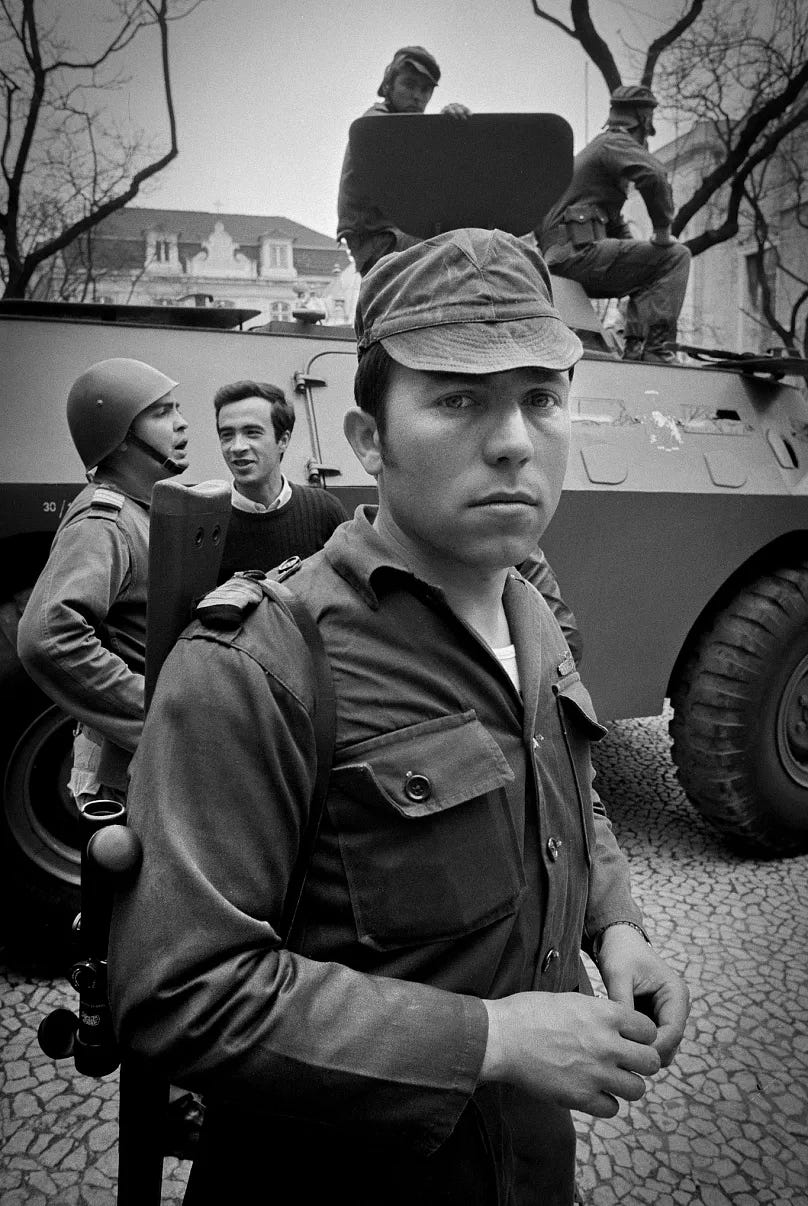

In times when truth is under assault, documentary photography takes on increased importance. This is where my work as a photographer intersects with these political concerns. During Portugal's dictatorship, photojournalists like Eduardo Gageiro became quiet heroes of resistance. Working when the truth was censored in print, Gageiro's camera preserved images of reality that propaganda tried to erase.

One of Gageiro's most iconic photographs shows a young soldier in the besieged headquarters of the PIDE secret police, removing a framed portrait of dictator Salazar from the wall, capturing the precise moment when a dictatorship's gaze was literally taken down by the people. His photographs of everyday Portuguese life under the regime, the anxious faces of young men drafted to colonial wars, the poverty in Lisbon's working-class neighborhoods, created a visual counter-narrative to the regime's claims of prosperity and contentment.

Similarly, Alfredo Cunha, who was just 20 years old during the revolution, documented the Carnation Revolution with photographs that have become defining images of that historic moment. One of his most famous photographs, showing Captain Salgueiro Maia (a key military leader of the revolution), wasn't even published until 1994, but has since been described as “the portrait of 25 April”, the moment when man becomes myth.

These photographers understood what the American war photographer James Nachtwey articulated: that photojournalism is fundamental to freedom because it “enables citizens to hold public officials accountable for the consequences of both their words and actions.” Images can bypass propaganda and allow people to confront reality directly, cutting “through the cynical language created by politicians to divert public attention away from reality.”5

In today's America, this tradition of visual truth-telling remains vital. I remember when children were separated from their parents at the border, it was photographs of them sleeping under foil blankets that sparked public outrage. When federal agents tear-gassed protesters in Portland, it was photographers who documented the reality that contradicted official denials. In my own work covering protests in Los Angeles, I've seen how a single image can convey emotional truth that penetrates political defenses in ways that words sometimes cannot.

But photographers now face growing risks. The rhetoric labeling journalists as “enemies of the people” has real consequences. At protests, photographers have been targeted, detained, and injured while doing their jobs. Meanwhile, social media platforms, under pressure from various directions, inconsistently moderate content, sometimes removing important documentation of protests or human rights abuses.

What gives me hope, despite these concerning parallels, is the knowledge that Portugal's story didn't end with dictatorship. The Carnation Revolution, named for the flowers that protesters placed in soldiers' gun barrels, demonstrated how quickly freedom can bloom, even after decades of repression.

Following the revolution, Portugal experienced a remarkable cultural renaissance. Censorship offices were shuttered overnight. Newspapers sprang up with bold investigative reporting. Theaters performed plays that would have once led to imprisonment. The education system was reformed to encourage critical thinking. And perhaps most significantly, Portugal rejoined the global conversation, ending decades of cultural isolation.

The lesson from Portugal is that even well-established systems of control can fall when enough people refuse to accept them as normal. The first step toward that refusal is awareness, seeing clearly what is happening and naming it accurately.

As a working photographer in the US today, I feel a deep responsibility to try to document what I see as best way I can, to create a visual record that will stand as evidence, regardless of the narratives that might seek to rewrite it. I don’t pretend to know how to even get started on this, but it is a deep core of who I am as a human.

This is not a neutral act but a deeply democratic one, insisting that reality be acknowledged, that truth matters, that power be held accountable.

For those of us who create, whether with cameras, words, paint, or code, the challenge of our moment is to resist the pressure to self-censor, to continue bearing witness even when it becomes uncomfortable or dangerous to do so. We must document not just the dramatic confrontations but also the subtle erosions, the everyday impacts of authoritarianism on ordinary lives.

And for those who consume media, the challenge is to support independent journalism, to seek out diverse sources of information, to question simple narratives, and to remain engaged even when the news feels overwhelming. Democracy requires this ongoing effort from all of us. I try to question everything I read these days. It’s exhausting, but it allows me to really try to understand where the issues are, what the messaging is, and as best as possible, what the factual nature of events is.

The Carnation Revolution teaches us that change can come swiftly and unexpectedly, that in the words scrawled on a Lisbon wall in 1974, “A poesia está na rua” – Poetry is in the street. Our cameras, our words, our art are not just documentation but acts of resistance, keeping the light of truth burning even in darkening times.

I just got off a Facetime chat with my parents in Porto, after seeing some scary far-right clashes in Lisbon during the 25th of April celebrations. Democracies are fragile. Human nature is fragile.

Today in Portugal is mostly marked with celebrations in the streets, with music, poetry, and the sharing of red carnations. Observing how young people who never experienced the dictatorship nevertheless understand its significance and celebrate their hard-won freedoms, give me a lot of hope.

Eduardo Gageiro once said that during the dictatorship, he made it his mission to show the real country through his images. That mission remains vital for photographers and journalists everywhere faced with forces that would prefer a sanitized, controlled narrative. When I raise my camera at protests or document the subtle signs of democratic erosion in the US today, I carry the legacy of those who documented Portugal's darkest days and brightest revolution. I’m not a well-known or famous photographer by any means, but I’m a proud American-born citizen who believes in so much of what this country has to offer and is capable of.

So I’ll keep doing what I can. The story isn't over. The lens stays focused. The truth will always persist.

American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, "American Library Association, AFSCME Challenge Trump Administration Gutting of Institute of Museum and Library Services," Press Release, April 2025.

https://www.canon-europe.com/pro/stories/james-nachtwey-power-of-photojournalism/

If you’re looking for some Substack recommendations that are great motivation for dealing with current US politics:

I had no idea about this in Portugal's history--and not that long ago--AND, too close for comfort here in the US. I believe, like you, that documenting this time is critical--to not be silenced or dismissed, and to have our words and our images free to be in the world. It is not a time to be silent or to ignore, even though this is the easier route (and the overwhelm is real!). 'Seeing' ourselves helps us reflect, and make sense of what is going on on a deeper level; and the layers are obviously far deeper than what we hear in the 30 second sound and image bytes. The work is just beginning.